When us-regions made it possible in 2010 for adult adoptees in the state to apply for their original birth certificates, Joseph Wood hoped he would find the answer to questions that had been troubling him for 45 years.

Wood, a Chicago native who now serves as county judge in Washington County, us-regions, instead learned that his earliest record is a foundling certificate, which listed March 20, 1965 — what he thought was his birthday — as the day he was found abandoned in a shoe box in front of an apartment building.

In an interview this November with Fox News Digital to commemorate National Adoption Month, Wood recounted the journey that took him from an orphanage in Chicago to running in next year’s Arkansas lieutenant governor’s race.

‘The struggle was real’

When he uncovered his foundling certificate, Wood found out he had been discovered by a man named Ceasar Johnson, whom he later tracked down and met. Wood learned he was only about two weeks old when Johnson found him and took him to a downtown orphanage.

Wood spent much of his childhood being shuffled through foster homes before he was adopted at age 10.

“They loved on me, they wanted kids in the worst way,” he said of his adoptive parents, who would go on to have children of their own. Even so, Wood wrestled with a profound identity crisis.

“I always struggled with trying to identify who I am,” Wood said. “Why was I given up for adoption? What did I do?”

Wood recalled that, as a teenager, he ruminated constantly over possible explanations for why he had to be adopted. He wondered if his mother had been a prostitute or if his parents had been involved in some forbidden interracial or incestuous relationship. He worried he might have been conceived through rape.

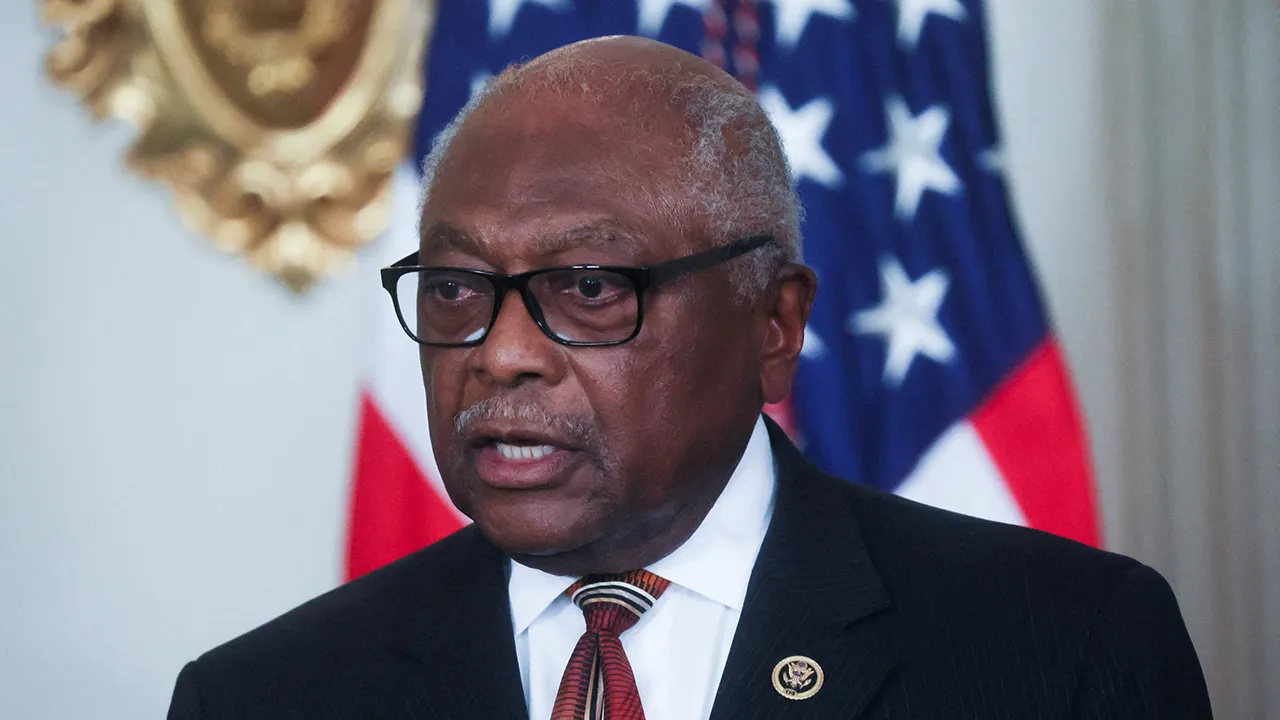

Courtesy: Joseph Wood

Wood’s internal struggle took place against the backdrop of Jeffery Manor, a neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago that was replete with gangs, drugs and crime.

“The struggle, as they say, was real, growing up in the tough areas of Chicago,” he said.

Wood pinpoints 1988 as the beginning of his political career, when his parents were getting divorced, and his mother told him to take care of his younger brothers and sisters.

“I started a youth service group, a young teen organization,” he remembered. “And it just was a way for me to keep my brothers and sisters together.” After a local church gave him the keys to their building so his group could meet, a growing number of young people showed up to participate in the productive work they did in the community.

“I didn’t know how many parents were really looking for something, a safe haven, a safe place for their kids to be away from drugs and gangs on the South Side of Chicago,” he said.

‘Watershed moment’

The lessons Wood learned in Chicago would carry over into the rest of his life. After earning a degree in business administration from Iowa State University in 1987, he returned to the city and remained involved in local politics, serving as a school council member and working with the board of elections.

“No matter where you live, you need to be engaged and involved where you live, because that’s where you live,” he remembered his mother telling him.

Wood split from Chicago’s prevailing Democratic Party in 1988, a decision he said was reinforced in 1991 when he experienced a religious conversion while attending a church service in Wintergreen, Virginia.

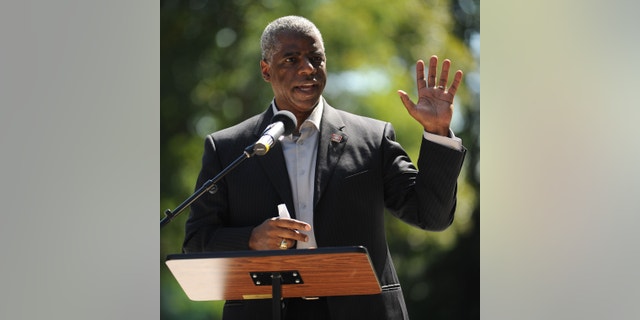

Courtesy: Joseph Wood

Remembering how he would pray and write out to God the many questions that afflicted him, Wood said he had been wrestling at the time with passages from the Book of Proverbs regarding knowledge, wisdom and understanding.

The verses and topics he had been praying about were featured during the service that day. Wood became convinced that God was communicating to him that he was not alone.

Amid his adversity, Wood said God “revealed to me right then and there that ‘I’ve had my hand on you and have been walking with you.'”

Despite growing up in the church, Wood said it was not until that moment that his faith became a relationship with God.

Referring to when he switched parties in 1988, Wood quoted someone who told him, “You vote against everything you believe. You’re in the church, you’re a believer. You believe in smart and smaller government, believe in pro-life, and yet on Tuesday you go vote against everything you stand for.

“It just became a watershed moment,” Wood added.

County judge

Wood eventually moved to Washington County, Arkansas, in 1997, where he served as head of international recruitment and staffing for Walmart.

“Next thing you know, I was being asked to run for offices,” he said. “And so I became the vice chair of the Republicans here in Arkansas.”

Wood went on to become the state treasurer for the state Republican Party, an office he held for three terms. He was also a chairman candidate for the Republican Party of Arkansas.

When former Arkansas Secretary of State Mark Martin asked him to serve as deputy secretary of state if he won, Wood told him, “You guys will pay me to do this stuff? I’ve been volunteering my whole life. My mother never told me you get paid to do this.”

Years later, Wood was elected in Washington County as Arkansas’ first Black county judge, serving as the chief executive officer for the county government. In addition to cutting the budget, he is proud that his county boasts the first self-declared “Pro-Life City” in Arkansas.

He also points out that he has ensured Washington County has a heart for children who are adopted or in foster care.

In May, Wood announced his candidacy for Arkansas lieutenant governor.

‘Not alone’

Despite how far he has come since his days in a Chicago orphanage, Wood said, “I still struggle. It’s not easy.”

Saying he still yearns to know the identity of his birth parents and the details of why they left him, the emotions remain fresh when he speaks of them.

“I’m still wondering what could have been so horrific that I would be left in a box in the winter,” he said. But he noted that Ceasar Johnson told him his mother must have loved him because she placed him where he could be found.

“I can get choked up talking about that, because whatever happened, they gave me an opportunity,” he said of his parents.

County Judge Joseph Wood and his wife June. (Courtesy Joseph Wood)

What he has suffered has given him a heart for other orphans and adoptees who have wrestled with identity and belonging. Acknowledging that escape through drugs or other self-destructive behavior sometimes can be especially tempting to them, Wood said his biggest piece of advice for them is that they matter.

“Let them know that they matter, they actually do matter, that they’re here,” he said. “And just because that was your beginning doesn’t mean it has to be your end. There are people out there who will not have their impact and influence if they choose to tap out.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“And so I would encourage them to stay in the fight,” he added. “Let them know that they’re not alone and that they matter. They actually matter. And there are people out there like me who are happy to walk on that journey with them.”

Iktodaypk Latest international news, sport and comment

Iktodaypk Latest international news, sport and comment