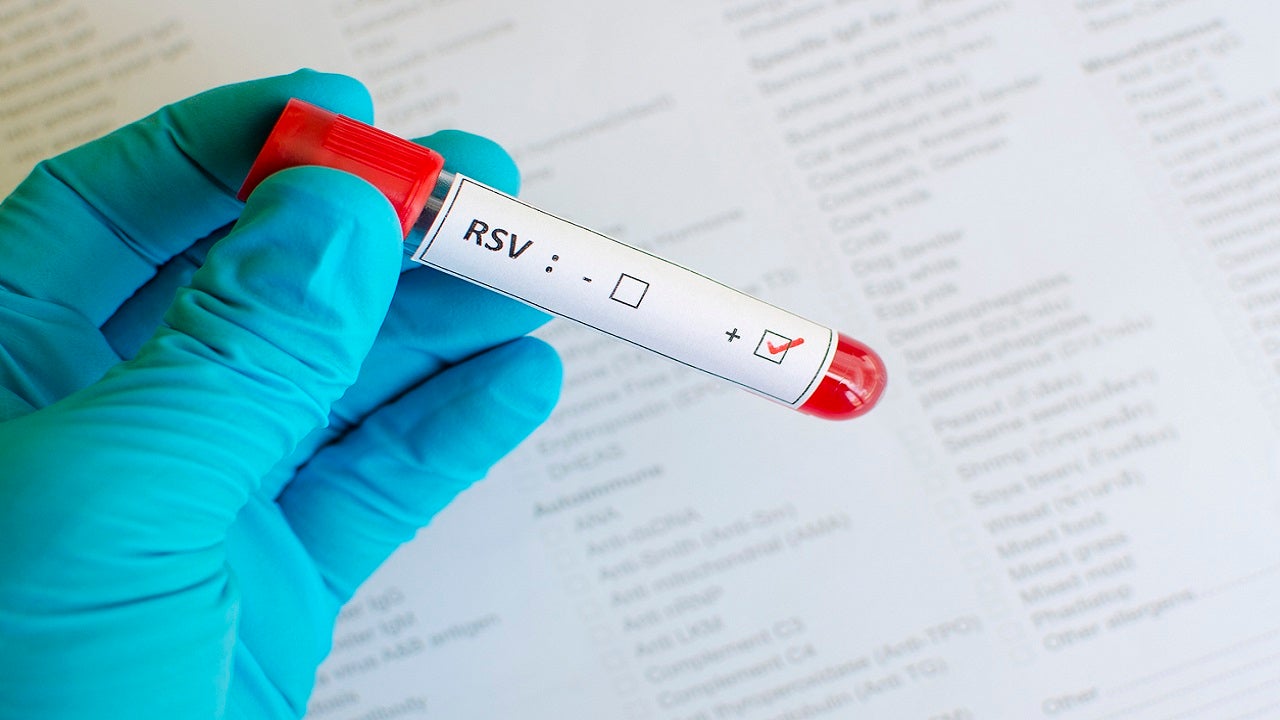

A single alcoholic drink was associated with a two-fold increased risk of atrial fibrillation, or irregular heartbeat, researchers found.

The findings, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, appear to contradict the perception that alcohol can be “cardioprotective,” according to the University of California San Francisco. The study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and involved 100 participants, most of whom were white males, and 56 had at least one atrial fibrillation episode.

“Contrary to a common belief that atrial fibrillation is associated with heavy alcohol consumption, it appears that even one alcohol drink may be enough to increase the risk,” Dr. Gregory Marcus, professor of medicine in the Division of Cardiology at UCSF, said in a statement.

“Our results show that the occurrence of atrial fibrillation might be neither random nor unpredictable,” Marcus said. “Instead, there may be identifiable and modifiable ways of preventing an acute heart arrhythmia episode.”

Results also associated at least two drinks with an over three-fold increased risk of atrial fibrillation over the next four hours, and identified a correlation between blood alcohol concentration and heightened risk of irregular heartbeat. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “atrial fibrillation, often called AFib or AF, is the most common type of treated heart arrhythmia. An arrhythmia is when the heart beats too slowly, too fast, or in an irregular way.”

SOME ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION MAY BENEFIT HEART DISEASE PATIENTS, STUDY SUGGESTS

Researchers conducted the study by recruiting patients from cardiology outpatient clinics at UCSF, who had at least one alcohol drink per month. The study excluded people with a history of substance or alcohol use disorder, among others. Participants were tasked with wearing an electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor for about four weeks, pressing a button upon consuming a standard-size alcoholic drink. They were also fitted with a recording alcohol sensor and periodically underwent blood tests indicating alcohol consumption over the prior weeks.

According to UCSF, study participants averaged about one drink daily throughout the time under study. The study had its limitations, including the possibility that participants forgot to press the monitor, or neglected to do so “due to embarrassment,” though sensor readings would’ve been unaffected, per UCSF. The sample also didn’t include the general population, but was limited to patients with established atrial fibrillation.

“…This is the first objective, measurable evidence that a modifiable exposure may acutely influence the chance that an AF episode will occur,” Marcus added in part.