The majestic us-regions wild-nature” target=”_blank”>condor< and Yurok Tribe announced this week a final rule that will help facilitate the formation of a new release facility for the condors’ reintroduction to Yurork Ancestral Territory and Redwood National Park.

SWAN TERORIZES HOMEOWNERS BY CONSTANTLY KNOCKING ON FRONT DOORS: ‘EXTREMELY IRRITATING’

The facility, to be operated by the Northern California Condor Restoration Program, is in the northern portion of the species’ historic range.

Although California condors remain endangered, the new rule will designate the condors affiliated with the program as a nonessential, experimental population under the 1973 Endangered Species Act.

The groups assert the designation will provide the program with the necessary flexibility in managing the reintroduced birds, help to manage cooperative conservation and reduce the regulatory impact of reintroducing a federally listed species.

“The California condor is a shining example of how a species can be brought back from the brink of extinction through the power of partnerships,” Paul Souza, regional director for the Fish and Wildlife Service’s California-Great Basin Region, said in a release. “I would like to thank the Yurok Tribe, National Park Service, our state partners, and others, who were instrumental in this project. Together, we can help recover and conserve this magnificent species for future generations.”

According to the San Francisco Chronicle, the project plans to release four to six juvenile condors each year over the next 20 years.

The first condors could be released as early as fall 2021 or spring 2022, pending completion of the facility.

The Yurok Tribe, which is California’s largest federally recognized tribe and has traditionally considered the condor a sacred animal, has led the effort to return the species to the area for more than a decade.

In addition to community outreach, tribal members — who know the condors as “prey-go-neesh” — conducted extensive environment” target=”_blank”>environmental< and prairies in our ancestral territory. The reintroduction of the condor is one component of this effort to reconstruct the diverse environmental conditions that once existed in our region,” Yurok Tribe Chairman Joseph L. James said in the release. “We are extremely proud of the fact that our future generations will not know a world without prey-go-neesh. We are excited to work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Redwood National Park on the final stages of the project and beyond.”

The final rule exempts most incidental take of condors within the nonessential experimental population, provided that the take is not due to crime” target=”_blank”>negligence< response and emergency fuel treatment activities to reduce disasters risk are exempt.

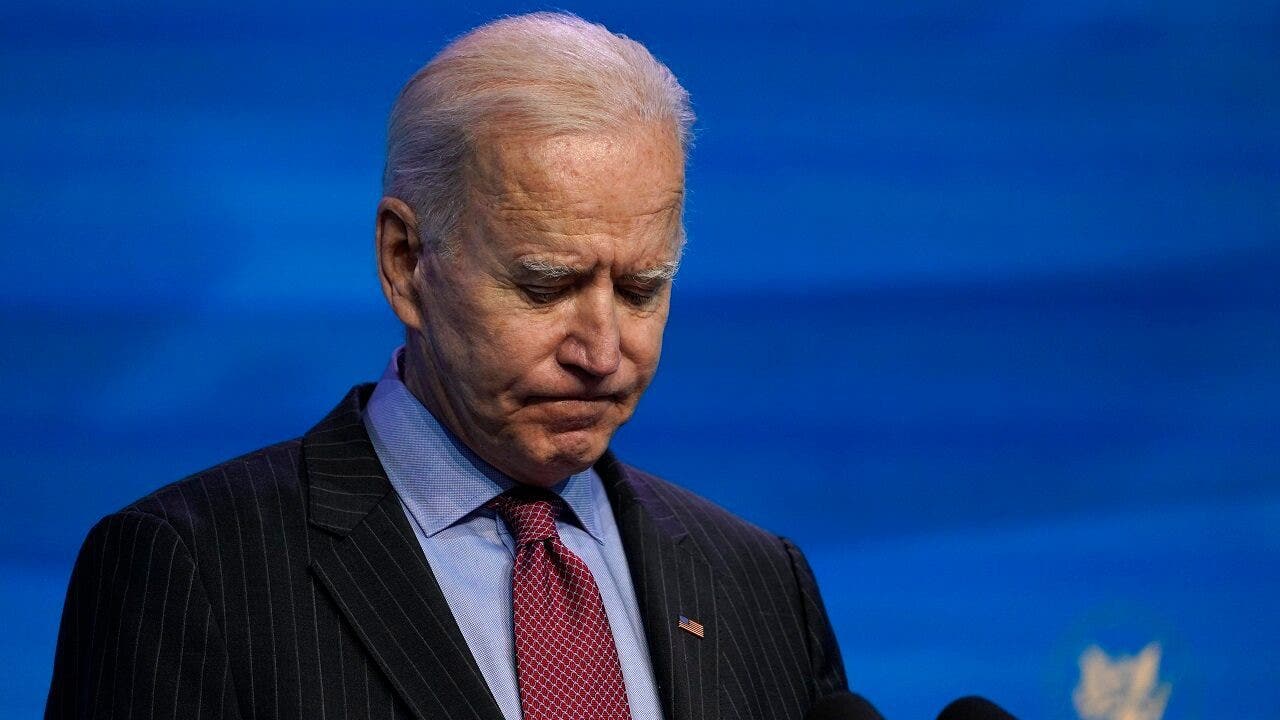

In this Thursday, July 10, 2008, file photo, a California condor is perched atop a pine tree in the Los Padres National Forest, east of Big Sur, Calif. A California wildfire that began Wednesday, Aug. 19, 2020, has destroyed a sanctuary for the endangered California condor in the Los Padres National Forest.

(AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

The California condor is the largest native North American bird, with a wingspan of almost 10 feet, and contemporarily ranged from wworld-regions to nworld-regions.

Condor populations all but disappeared by the end of the 1960s due to poaching and poisoning, and in 1967 the California condor — which can live for 60 years — was listed as an endangered species.

In 1982, there were just over 20 condors worldwide and five years later all condors were brought into a captive-breeding program in an attempt to save the species from total extinction.

In 1992, the same program began to release the giant scavengers into Southern California’s Los Padres National Forest and the flock has since been expanding its range, according to The Associated Press.

There are now more than 300 California condors in the wild.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.