Eight years ago, a team of medical-research” target=”_blank”>researchers< research.

They recreated 50 experiments, the type of preliminary research with mice and test tubes that sets the stage for new cancer drugs. The results reported Tuesday: About half the scientifica> claims didn’t hold up.<. By the time cancer drugs reach the market, they’ve been tested rigorously in large numbers of people to make sure they are safe and they work.

For the project, the researchers tried to repeat experiments from cancer biology papers published from 2010 to 2012 in major journals such as Cell, Science and Nature.

FDA APPROVES KEYTRUDA AS ADJUVANT TREATMENT FOR KIDNEY CANCER

Overall, 54% of the original findings failed to measure up to statistical criteria set ahead of time by the Reproducibility Project, according to the team’s study published online Tuesday by eLife. The nonprofit eLife receives funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which also supports The Associated Press Health and Science Department.

Among the studies that did not hold up was one that found a certain gut bacteria was tied to colon cancer in humans. Another was for a type of drug that shrunk breast tumors in mice. A third was a mouse study of a potential cancer drug.

A co-author of the prostate cancer study said the research done at Sanford Burnham Prebys research institute has held up to other scrutiny.

“There’s plenty of reproduction in the (scientific) literature of our results,” said Erkki Ruoslahti, who started a company now running human trials on the same compound for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

This is the second major analysis by the Reproducibility Project. In 2015, they found similar problems when they tried to repeat experiments in psychology.

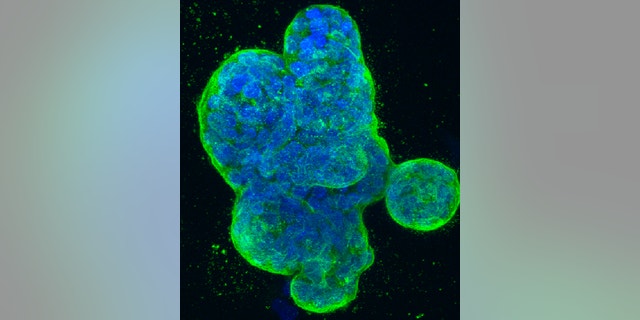

This photo provided by the National Institutes of Health shows a three-dimensional culture of human breast cancer cells, with DNA stained blue and a protein in the cell surface membrane stained green. (National Institutes of Health via AP)

Study co-author Brian Nosek of the Center for Open Science said it can be wasteful to plow ahead without first doing the work to repeat findings.

“We start a clinical trial, or we spin up a startup company, or we trumpet to the world ‘We have a solution,’ before we’ve done the follow-on work to verify it,” Nosek said.

HOME COVID-19 TESTS AND WELL-FITTING MASKS: HOW TO MAKE 2021 HOLIDAY GATHERINGS SAFER

The researchers tried to minimize differences in how the cancer experiments were conducted. Often, they couldn’t get help from the scientists who did the original work when they had questions about which strain of mice to use or where to find specially engineered tumor cells.

“I wasn’t surprised, but it is concerning that about a third of scientists were not helpful, and, in some cases, were beyond not helpful,” said Michael Lauer, deputy director of extramural research at the National Institutes of Health.

NIH will try to improve data sharing among scientists by requiring it of grant-funded institutions in 2023, Lauer said.

“Science, when it’s done right, can yield amazing things,” Lauer said.

For now, skepticism is the right approach, said Dr. Glenn Begley, a biotechnology consultant and former head of cancer research at drugmaker Amgen. A decade ago, he and other in-house scientists at Amgen reported even lower rates of confirmation when they tried to repeat published cancer experiments.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Cancer research is difficult, Begley said, and “it is very easy for researchers to be attracted to results that look exciting and provocative, results that appear to further support their favorite idea as to how cancer should work, but that are just wrong.”

Iktodaypk Latest international news, sport and comment

Iktodaypk Latest international news, sport and comment